By James Shepherd MD PhD

Yale University School of Medicine

Est Read Time: 6 minutes

You might think that a garden full of native plants, thicker on the ground and under the trees, jumbled together in profusion, might be a better habitat for disease-carrying ticks, bugs, and mice than a closely cropped lawn of turfgrass in a neat suburb with lots of "Garden Center" landscaping. Intuitively, the neat and managed neighborhood looks like the sort of place where infectious diseases couldn’t thrive. The experience of the last few decades in southern New England would suggest otherwise!

How Human Development Fueled the Spread of Lyme Disease

Lyme Disease, a bacterial infection transmitted by the bite of the black-legged deer tick, has dramatically spread in the region over the last 50 years. The bacteria, the tick vector, and the natural hosts – deer, mice, and birds – were all present before humans arrived in North America. The explosion in human cases, first detected in the 1970s, was fueled by human environmental changes. Development, suburbanization, the introduction of invasive plants, and habitat fragmentation disrupted the native biome. Some species thrived in human-created environments in southern New England - white-tailed deer, white-footed mice, and robins, for instance - and with their success, their infections and parasites have also proliferated. Borrelia burgdorferi, Anaplasma cytophilum, Ehrlichia chafeensis, Babesia microti and Powassan virus succeeded in this new human-made environment along with their transmission vector, the black-legged tick, which bites a variety of warm-blooded hosts and spreads the infectious wealth around.

Why Invasive Plants Create Perfect Tick Habitat

Of course, ticks do not discriminate between warm bloods. They will bite anything that brushes them off an understory twig in order to get a bloodmeal. They favor bushes where deer walk and mice live, humid and protected. Their favorite bush around here is Japanese Barberry, an imported escapee from the landscaped suburbs and perfect habitat for mice, ticks and deer. For millennia this natural cycle of infection was presumably quite stable until human development created new habitat that cleared native environments and replaced them with a diminished variety of species that suited our purpose.

Japanese Barberry, Berberis thunbergii, is an invasive shrub that is a favorite of mice, ticks, and deer.

The Dilution Effect: How Biodiversity Protects Us

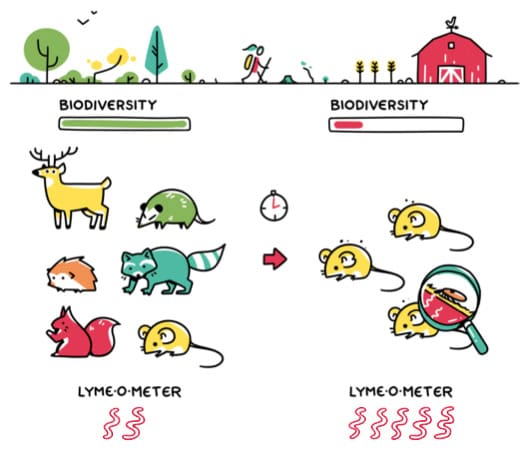

The inverse relationship between biodiversity and transmission of infectious diseases is an established ecology concept called “The Dilution Effect”. As biodiversity declines the most able species that take advantage of this are those that tend to reproduce rapidly, adapt quickly to denuded habitat, and also tend to be good hosts for infectious organisms.

Our Fragmented World: A Hotspot for Disease

And here we are. Living in a fragmented world that works for us but not so well for most other species. But it turns out these fragmented, human-shaped landscapes are ideal for the spread of diseases that jump from animals to people. Animals like mice and ticks thrive when predators disappear and forests are broken up. Our rates of tick-transmitted infections have risen sharply over the last few decades and Lyme Disease is spreading from the northeast into new areas across the east and northwards into Canada. Another environmental factor created by us – warming – has allowed expansion of black-legged ticks into Canada but also allowed new tick vectors to move into our neighborhood from the south. Lone Star Ticks, Longhorned Ticks and Gulf Coast Ticks are now breeding along coastal Connecticut and will surely take advantage of our man-made habitats as they spread northwards. They carry new diseases that are beginning to emerge in new areas. Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever, Rickettsia parkeri, Alpha-gal Meat Allergy, Heartland Virus, and quite a few more!

How Biodiversity Can Help Limit Disease Spread

What would limit this march of infectious diseases into new regions? Biodiversity! Imagine a mouse or a deer or a tick or a mosquito migrating into a new habitat. If a place is already full of a healthy mix of native wildlife (everything from bugs to birds to mammals) it’s harder for an outsider species to take over. There’s just too much competition from the locals. The best way to crowd our neighborhood with abundant neighbors is to create native environments favored by locally adapted species.

Practical Steps: Planting for Healthier Landscapes

Oaks, maples, hawthorns, spicebush, sassafras, goldenrod, milkweed, native grasses, legumes, and more are favored host plants of our local biome in Connecticut. If we plant them and connect them with our neighbor’s plantings, we may limit disease hosts and vectors in our gardens. If we connect more of these native and biodiverse habitats into bigger and bigger areas capable of sustaining the full food chain, then we may expect to see a decline in the rapid rise of zoonotic infections, old and new, that have plagued us in the last few years. The turfgrass lawn and the mulched rhododendrons aren’t as safe as they look.

Editor’s Note:

As part of our effort to expand the conversation around native plants and the biodiversity movement, we are inviting guest contributors with expertise in related fields. These pieces are intended to spark discussion and deepen understanding of the complex systems that shape our natural world.

This article is focused on how healthy ecosystems function — specifically, the theoretical relationship between biodiversity and overall tick populations. It is not intended to address individual exposure risk or offer personal health guidance.

We recognize that personal risk of tick-borne illness is shaped by many factors, and that people may still encounter ticks in highly manicured environments. This piece does not attempt to weigh in on public health practices or safety recommendations. Instead, it explores how changes in land use and biodiversity loss may contribute to broader patterns in disease ecology.

Try Our Keystone Plant Tool!

Find the most productive plants for YOUR region.