Nesting Sites and Soft Landings

Planting native plants, especially keystone species, invites insects and other wildlife to our wildlife landscapes. As these plants become established in our landscapes, we can see the truth in the saying, “Plant them and they will come!" But how can we encourage our new visitors to remain and become thriving residents in our wildlife habitats? It's actually rather simple: Provide wildlife with food, water, shelter, and places to reproduce.

In this action, we focus on places to reproduce including how to preserve and create pupation sites for caterpillars, wasps, beetles, and other insects and how to encourage nesting sites for bees, birds, and other creatures throughout your landscape.

Pupation sites also called soft landings, are planted areas under trees where caterpillars drop to the ground and pupate along with other beneficial insects. The true measure of a rich, supportive wildlife habitat is the presence of pupating and nesting creatures!

Learn to recognize pupation and nesting sites and the different life stages of insects

Nesting & Overwintering Habitat (free, 12-page PDF): Produced by the Xerces Society, this informative guide shows clear images of the different stages of the life cycles of pollinators and other beneficial insects along with illustrated steps for creating nesting and overwintering habitat. To find this guide, visit the Xerces Society website (xerces.org). In the search bar, enter nesting & overwintering habitat. Scroll through the results until you see this title and click on it, or search online for xerces nesting & overwintering habitat.

Bumble bees: For an illustrated diagram of the life cycle of bumble bees, visit the Xerces Society website (xerces.org). In the search bar, enter life cycle bumble bee. Click the article About Bumble Bees for an illustrated diagram of the bumble bee life cycle and click Bumble Bees: Nesting and Overwintering for exquisite photos of nesting bumble bees. While on this site, check out the other helpful articles about bumble bees that are well worth reading.

Butterflies and moths: Different life stages of a single species of Lepidoptera may have completely different appearances. Consider, for example, the black swallowtail whose young caterpillar is black with orange dots and spots and a white saddle (far left). It develops into a smooth bright green and black striped caterpillar with yellow spots (left); later it becomes a black and white butterfly that even has some blue markings (right).

Butterflies and moths: Different life stages of a single species of Lepidoptera may have completely different appearances. Consider, for example, the black swallowtail whose young caterpillar is black with orange dots and spots and a white saddle (far left). It develops into a smooth bright green and black striped caterpillar with yellow spots (left); later it becomes a black and white butterfly that even has some blue markings (right).

Life cycles of other insects and creatures: Search online for images with the terms life cycle [animal's name], for example "life cycle dragon fly." Typically, both diagrams and photographs will come up. Shown at left is a dragonfly exuvia (the cast-off skin of a dragonfly larva). A fascinating book The Secret Lives of Backyard Bugs: Discover Amazing Butterflies, Moths, Spiders, Dragonflies, and Other Insects! by Judy Burris and Wayne Richards is an engaging resource when it comes to getting familiar with the life cycles of insects such as butterflies, moths, beetles, ants, grasshoppers, aphids, and even the black widow spider.

Recognizing nesting sites of insects and creatures: Search online for nesting site [animal's name]. Typically, the first result will describe the preferred nesting site or habitat for this creature. For photos or diagrams, search for images using the same search terms.

Explore the Butterflies and Moths of North America (BAMONA) website to learn to recognize the different life cycle stages of Lepidoptera species

Now, we'll take a close look at the Butterflies and Moths of North America (BAMONA) website. Here, you'll find informative profiles of Lepidoptera (butterflies, skippers, and moths) that include historic and current range maps, life history, caterpillar host plants, adult food sources, habitat, conservation status, and much more including numerous photos of documented sightings and high-quality images of caterpillars. BAMONA will even help you identify a butterfly or moth. This is a remarkable resource!

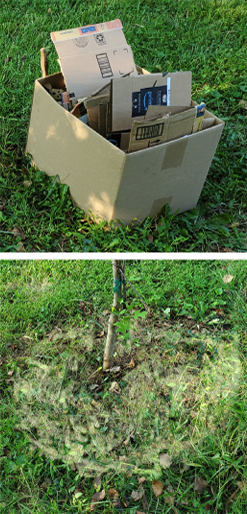

Create caterpillar pupation sites under the trees and shrubs on your property

When a fully grown caterpillar drops to the ground, it will either spin a cocoon in the leaf litter under the tree, or it will burrow into the soil to pupate underground. The soil must be loose and protected from disturbance until the pupa emerges as an adult. Landscape beds can serve as pupation sites; in contrast, the soil under a tree located in the middle of a mowed lawn is compacted and inhospitable to caterpillars. Luckily, it’s not difficult to create pupation sites under trees and shrubs. If you have an existing tree or shrub, remove any lawn to at least the tree's drip line (an imaginary line around the farthest reaches of the leaf canopy). Choose a lawn removal method described in Action 3: Shrink the Lawn other than the Bake It! method which could overheat the surface roots of trees or shrubs. Shown below are the steps for using the Block It! method to create a caterpillar pupation site around a tree growing in the middle of the lawn.

Step 5: As soon as resources permit, densely plant the area with keystone plants and plants needed by specialists. While waiting for plantings to get established, fill in any gaps with leaf litter or regionally appropriate mulch. Any cardboard that remains will break down over time and mix in with the mulch.

Protect and support caterpillar pupation sites throughout the year

Once you've set up a pupation site, take these important actions to support caterpillars throughout their pupation:

Grow native plants and maintain a layer of leaf litter on all your pupation sites to provide critically needed shelter for pupating caterpillars.

Grow native plants and maintain a layer of leaf litter on all your pupation sites to provide critically needed shelter for pupating caterpillars.

Add and arrange some rocks and logs or branches in a pleasing design. Include piles of rocks and stacks of logs wherever possible.

Add and arrange some rocks and logs or branches in a pleasing design. Include piles of rocks and stacks of logs wherever possible.

Avoid disturbing the leaf litter and plants growing in pupation sites.

Avoid disturbing the leaf litter and plants growing in pupation sites.

Avoid walking on pupation sites. Borders help prevent people from accidentally trampling on pupation sites.

Avoid walking on pupation sites. Borders help prevent people from accidentally trampling on pupation sites.

Don’t mow pupation sites. Mowing not only crushes pupae, but it also compacts the soil making it impossible for caterpillars to burrow into the soil.

Don’t mow pupation sites. Mowing not only crushes pupae, but it also compacts the soil making it impossible for caterpillars to burrow into the soil.

When the leaves drop from your trees, wherever possible, leave the leaf litter. Leaf litter is nutrient-rich "gold" in a wildlife habitat. Some caterpillar species feed on fallen leaves. As leaves decompose, they form a rich layer of duff (decaying organic matter) that provides an ideal habitat for pupating caterpillars, overwintering native bee larvae, and many other small creatures. A layer of duff keeps the soil moist and loose for caterpillars that pupate below the soil surface and bees that excavate underground nests.

Wherever possible, leave a tree's own fallen leaves in place extending all the way out to the tree's drip line to a depth of about 2 inches. Avoid raking the leaves into a pile around the base of a tree trunk!

Composted leaf litter, called leaf mold, is a rich soil amendment that supports micro life. Adding moisture to a leaf pile and turning it every so often is all that’s required to produce leaf mold—your bucket of gold!

Caution: To prevent smothering of plants, clear leaf litter away from low-growing ground covers such as mosses, sedges (Carex), pussytoes (Antennaria), and moss pink (Phlox subulata) and away from plants with basal rosettes such as cardinal flower (Lobelia cardinalis).

Leave stumps and dead trees (when safe) and place wood stacks, brush piles, logs, and large rocks all around your property

Wherever possible and when it's safe to do so, leave dead branches and snags (dead trees) standing and leave fallen trees and stumps in place on the ground. Many insects and other organisms that play a critical role in the food web feed and reproduce on deadwood. For example, the pileated woodpecker shown here depends primarily upon carpenter ants and other wood-boring insects who inhabit deadwood. Deadwood also offers reproduction sites for species of cavity-nesting birds and some species of native bees and other creatures. The very survival of these animals depends on the availability of rotting wood, deadwood, or existing cavities!

With a mature height measuring 16 to 19 inches, the pileated woodpecker (Dryocopus pileatus) is the largest woodpecker in North America. Deadwood provides the insects and shelter this woodpecker needs to survive.

There is nothing like a wood stack or pile of branches to provide shelter for insects, small birds, and other creatures along with habitat for fungi and micro life in the soil. Place the pile somewhere hidden from view at least ten feet away from any buildings. Consider planting a screen around the pile to hide it from view. T he Xerces Society suggests highlighting your pile with a Pollinator Friendly Habitat sign “to advertise your good intentions to your neighbors" (see page 6.12). Not every property can accommodate the invaluable wildlife resource of deadwood, but hopefully yours can!

Supply safe nesting places for native bees: deadwood, bare ground, and pithy and hollow plant stems

Ensuring that native bees in your wildlife habitat have safe nesting places, though not difficult, requires some planning. Unfortunately, mismanaged artificial bee nests can lead to predation and disease in native bee populations. By providing deadwood, bare ground, and pithy or hollow plant stems, artificial bee nests are unnecessary (and Mother Nature does the housekeeping for you!)

Supply well-situated bare ground for ground-nesting native bees

Approximately 70% of native bees are ground-nesters that excavate burrows underground. To support these bees, f ind an out-of-the-way place on your property where they can nest undisturbed. Ideally, the area should be well-drained with sparse vegetation and sandy or loamy soil that is friable (you could scoop it with a spoon—if you had to for some reason!), although some native bees readily nest in compacted soil. Patches of thin layers of small pebbles or a few small rocks create attractive crevices. A gently sloped site is especially attractive to some bee species. Keep an eye out for small mounds of soil and bee activity.

Unlike ground-nesting yellow jackets, which are a species of wasp, ground-nesting native bees don't sting unless they are seriously provoked at their nesting site. Mostly it is male native bees that hover around the nest, and they don't even have stingers. Discovering native bees nesting in your wildlife habitat is cause for celebration!

Manage pithy and hollow plant stems to optimize safe nesting places for native bees

When the urge hits to clean up the garden in the fall and spring, resist the temptation to clear out the garden debris. Instead, help ensure the survival of native bees by leaving the stems and canes of perennial plants to provide nesting sites for native bees. Here's how to do this:

YEAR 2—Summer and beyond: Foliage will begin to cover the cut stems. Be on the lookout for signs of bees excavating the pith from stems (above right). Different bee species will nest and emerge at different times of the year, so be sure to leave the dead stems standing.

YEAR 3: Continue to leave the Year 1 stems (cut in Year 2) standing until they decompose naturally. By now several generations of stem-nesting bee species may have used these stems. Some bee species reuse the stems from previous years. Decomposition of the stems helps to naturally prevent the spread of disease that could come from continual reuse. In spring, cut the stems of Year 2 growth—thus, the cycle begins anew!

Leaving stems is much easier than it sounds!

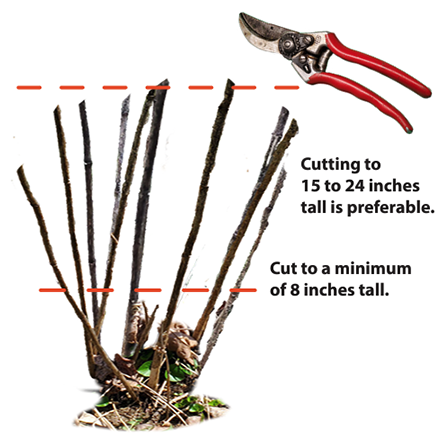

Simply:

- Wait until spring to cut back stems.

- Cut stems to various heights, ideally between 15 to 24 inches and no shorter than 8 inches.

- Leave the stems in the garden until they decompose (or stack them in a hidden place).

- Repeat annually.

If you live in a neighborhood with rigid aesthetic standards, you may have no choice but to cut stems to 8 inches. This looks tidy and new foliage will quickly cover last year's stems. If possible, take the cut pieces of stem and stack them upright in a hidden area of your property—the bees may still use them.

A treasure trove of pollinator resources:

For exquisite photos and an illustrated chart showing the life cycle of stem-nesting bees, visit Heather Holm's website: pollinatorsnativeplants.com and click on Plant Lists & Posters. Here you will also find wasp fact sheets and other high-quality charts such as Trees and Shrubs for Pollinators.

Grow native plants that produce pithy or hollow stems for stem-nesting bees

Approximately 30% of native bees excavate cavities or use existing cavities in deadwood, stone crevices, or plant stems. Intentionally planting native plants that have pithy or hollow stems will go a long way toward attracting and supporting these native bees. As we just discussed, the other half of the equation is proper management of the stems. Here are examples of plants that provide pithy or hollow stems:

Native Forbs:

Native Vines and Shrubs:

The Lady Bird Johnson and Xerces Society Plant Database for Pollinators offers a handy list of plants that provide nesting materials for native bees. Visit wildflower.org/project/pollinator-conservation. Scroll down to Resources. Click on Plants of Special Value to Beneficial Insects. Click on Provides Nesting Materials/ Structures for Native Bees. Use the filters to narrow your search.

You will recognize many of these plants as keystone plants. They hold the promise of becoming luxurious multi-unit housing for stem-nesting bees. Next, we'll look at managing and planting your landscape to encourage birds to stay and nest

Encourage birds to nest in your wildlife landscape

Finding a bird nest in your wildlife habitat is always exciting. Plus, it's a sign that your ecosystem is functioning! Employing bird-friendly ecological management practices, such as leaving deadwood standing and growing native plants, will encourage birds (and the insects they depend on) to live on your property. Cavity-nesting birds often reject human-made cavity nest boxes. If a cavity-nesting bird cannot find a suitable nesting site, it will fail to breed that season.

The shortage of cavity sites is exacerbated by the presence of invasive species of birds, such as the house sparrow (Passer domesticus) and European starling (Sturnus vulgaris), that attack some cavity-nesting bird species further reducing their reproductive success.

This cavity-nesting red-bellied woodpecker (Melanerpes carolinus) relies on soft or deadwood to excavate its nest. Even when it finds deadwood large enough to accommodate its cavity, it must fend off attacks from sparrows and flocks of starlings to protect its eggs and raise its young.

Strategies for inviting nesting birds to your wildlife landscape:

This content is an excerpt from Nature's Action Guide by Sarah F. Jayne, shared here with the author’s permission. All rights reserved © 2024 Sarah F. Jayne.